All that’s rare is not gold: The Scarcity heuristics in UX design

Scarcity heuristics can lead us to place a higher value on goods that we consider rare or limited in terms of quantity, time or accessibility. As you will see, this is undoubtedly a very powerful way of leveraging consumers, and UX designers are very well aware of it. But, just as it is not all gold that glitters, it is not always more precious what is scarce. And consumers are becoming fully acquainted of this. So, although leveraging cognitive biases is definitely one of the trends of the last decade, we mustn’t forget the importance of contextual and individual factors and, in particular, the effects that such strategies can have in the long run.

If you’re here, it’s because you love or you’re fascinated by behavioral economics. If so, you might already know what heuristics are, and the cognitive biases they trigger. And you might also know why we get tricked by those fallacies. And you’ll also know that our judgements (or biases), while not necessarily corresponding to the evidence but only to the subjective interpretation of the information in our possession, are, nonetheless, fundamental shortcuts for making sense of (and surviving in) our environments.

All of the professionals involved in designing processes, experiences and paths of some sort are very well aware of both the errors of evaluation and the lack of objectivity in the judgments that people make on a daily basis. So, in a certain sense, they work in order to act so as to either eliminate them or leverage them, depending on their objectives.

So, everything that is designed with the user-interaction in mind must include a deep understanding of users’ cognitive biases. On the one hand, information architects can decide to leverage them for the users’ own good; let’s think about the recent “Twitter Warning” that we get if we try retweeting a link to a news article that we didn’t even open, and that nudges us away from a mindless sharing activity. On the other hand, marketing-oriented UX design strategies don’t just understand heuristics and cognitive biases to make sure that the user gets the best experience possible out of their online experience. They do it to leverage our biases and cognitive shortcuts so as to increase conversions, guiding customers towards the businesses’ desired outcomes, so as to increase profitability. But that’s no surprise, and users are also becoming wiser and wiser to such nudges.

And this is definitely the case of scarcity, that some are leveraging to such an extent that we now tend not to take it seriously, as we know that it’s just another ace up the seller’s sleeve.

Defining Scarcity

When an object or resource is less readily obtainable or available, we tend to ascribe more value to it (Cialdini, 2001). Messages of scarcity alarm us and indicate that there is a reduced or limited opportunity to purchase the product we desire (Lynn, 1989) and, for that reason, we tend to act impulsively to obtain it.

So, creating an “uncertainty” around the product, be it in terms of quantity, time or accessibility to the product itself, can significantly affect the purchase intention. However, let’s not forget that there are many variables that mediate and moderate this effect, both at the individual level, such as competitiveness, narcissism, economic myopia, or the need for uniqueness, and at the contextual level, from the composition of the message to the influence of the brand concept (Aggarwal, Yun, and Huh, 2011).

So far we haven’t said anything new, so let’s just borrow a couple of examples from the restaurant industry. Small portions in an expensive restaurant increase the sense of sophistication, limited availability and prestige of the ingredients just as an almost full restaurant will seem more appealing to us than a completely empty one.

A set of biases

Why is scarcity so effective? Precisely because it leverages our inherent loss aversion. As we said, the scarcity heuristic is composed of many factors: knowing how it interacts with other cognitive biases, especially for UX design, doesn’t mean simply applying them all and throwing them into the sea of the web, but it means being able to balance them and use them to one’s advantage without over-stressing the user.

Scarcity and loss aversion

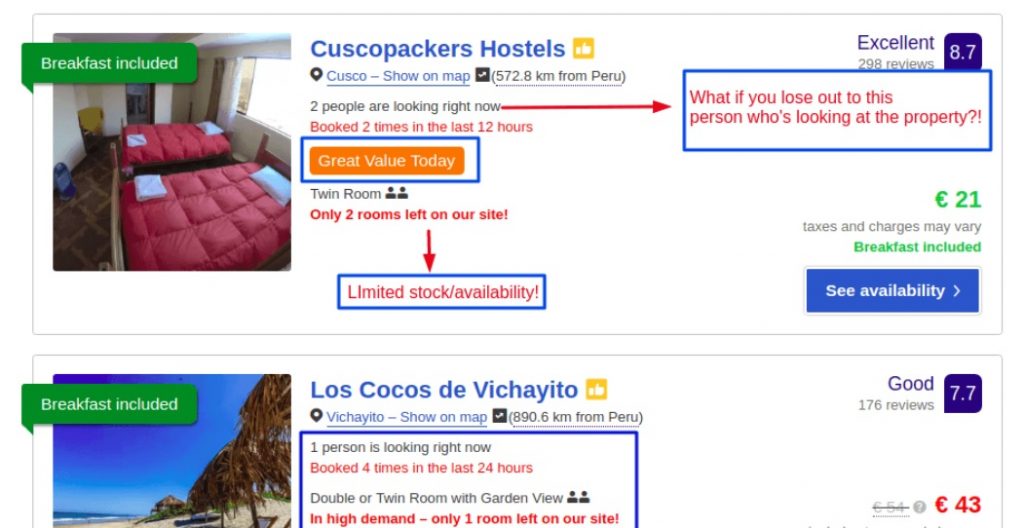

Without a doubt, scarcity is so effective because it leverages our loss aversion. In fact, a common practice of many online marketplaces is precisely that of showing – among the set of available alternatives – even those products that are already sold out. This trick gives us a preview of what it means to miss the opportunity to buy what we’re looking at.

Scarcity and social proof

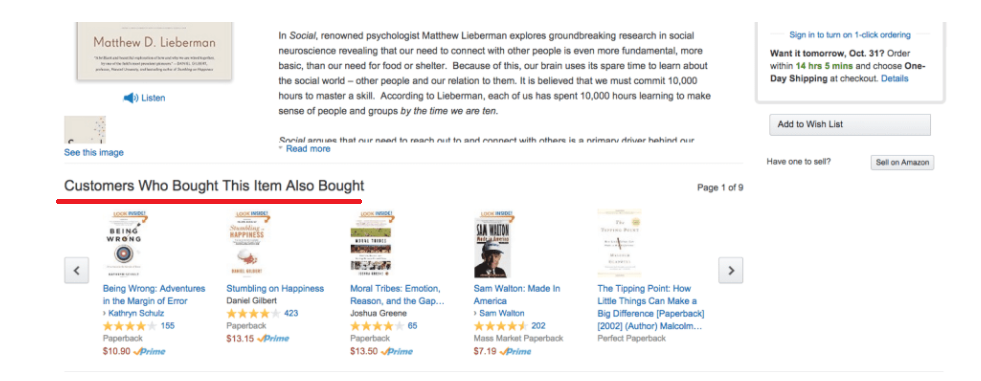

Generally, we tend to consider the behaviors and choices made by other people as more valid. Social proof is at the base of the very concept of fashion and, more recently, of the electronic word-of-mouth phenomenon, of peer-to-peer reviews as well as of the phenomenon of influencers on the web.

Providing numerical indications of scarcity, and in particular of the number of users who have previously purchased/booked, has a positive effect on the consumer’s decision to proceed with an online purchase.

Scarcity and regret aversion

To mediate the purchase decision (together with other factors such as perceived value), we have anticipatory regret. In choices under conditions of uncertainty, in which the effects of our decision will be known only after we have made it, we often find ourselves in a situation of remorse or regret after the fact. This unpleasant feeling, sometimes very painful, is called regret. The theory of regret aversion or anticipatory regret tells us that, when we make a decision, we anticipate regret and incorporate it into the decision-making process, during the evaluation of alternatives. This regret aversion makes us prefer choices that decrease the possibility of experiencing this unpleasant emotion in the future.

In the picture, using the example of booking.com, it is evident how scarcity leverages both social proof (51 bookings in the last 24 hours) and regret aversion (Only one room left on our site!): there is only one room left, so we are likely to be discouraged from procrastinating and induced to book, to avoid a future regret.

Many forms of scarcity

As you might have noticed from the examples presented so far, the concept of scarcity is not only limited to scarcity in terms of quantity, but also in terms of time and, let’s add, accessibility.

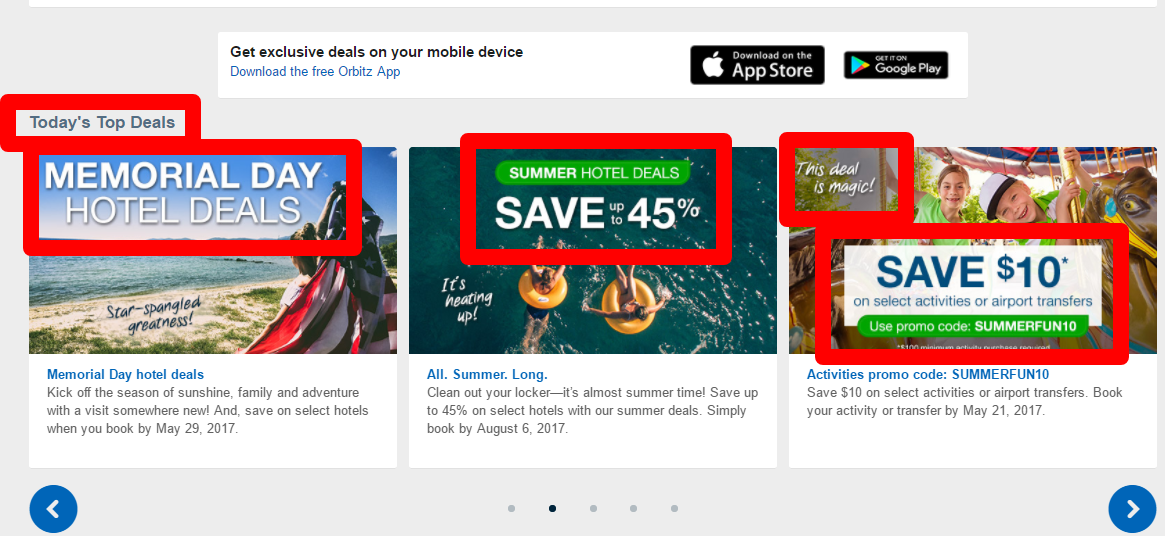

Let’s immediately give some examples of how UX design leverages these three types of scarcity within an online sales funnel.

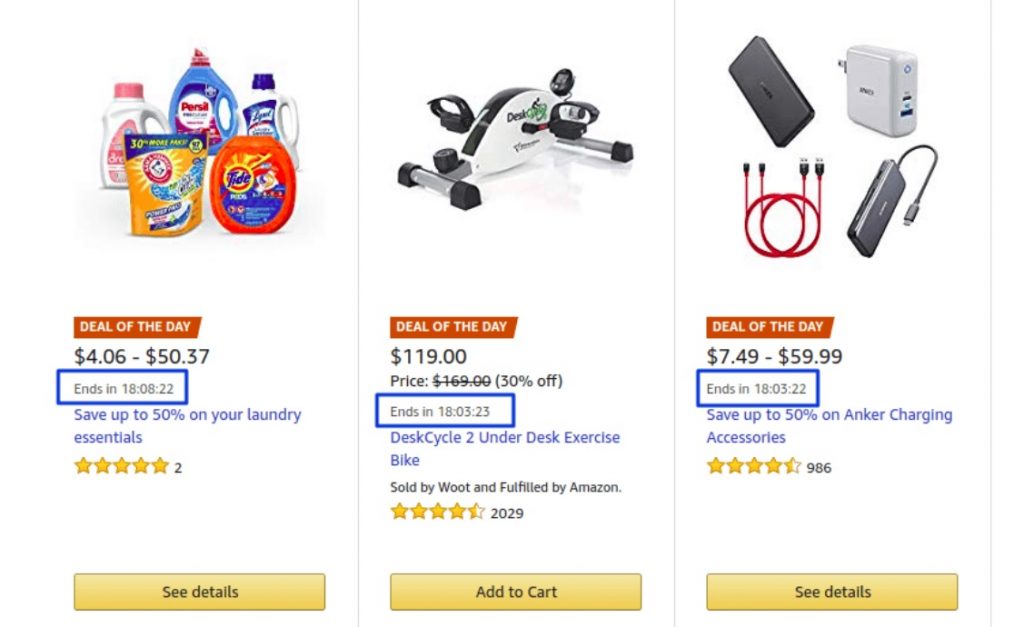

Scarcity in terms of Time

Regarding scarcity in terms of time, we can distinguish two cases in turn: the case where the deadline is known and the case where the deadline is hidden.

However, although marketing often outperforms scientific research in terms of application, one must always ask the right questions before implementing one choice rather than another.

First, what are the long-term risks? The second case, in fact, certainly leverages heavily on loss and regret aversion: with an unknown deadline, the only safe way to act and, thus, avoid guilt and loss, is to act now. “In two minutes” may already be too late.

But are we willing to take this risk without knowing what effects such a strategy may have on core factors of our brand, such as brand empathy?

Scarcity in terms of Quantity

The same happens with quantity: we can indicate how many pieces are left or we can decide to keep it hidden.

The case of e-bay is emblematic: a time icon tells us that the offer is about to end, but we don’t know when. The same happens with quantity: red writing warns us that the product is almost sold out. By clicking, we can know how many pieces have been sold, but not how many remain, leaving us with a sense of incomplete information.

Another example that David Teodorescu, UX Designer, defines as a “sneaky” way to leverage scarcity is the one often adopted by clothing marketplaces, as we mentioned before: products, models, colors and especially sizes that are not available are also reported, precisely because they increase the sense of scarcity of the product. And who among us, faced with a more extreme size, such as an XS or an XL sold out, has never opted for an intermediate size in order to have the product?

Scarcity in terms of Accessibility

A final example of scarcity is in terms of accessibility. James Gleick, in “Information. A history. A Theory. A Flood”, elegantly explains what has happened on the web:

We have become accustomed to associating value with scarcity, but in the web this is no longer the case. You can be the sole owner of a Jackson Pollock or a rare bottle of Blue Mauritius, but you can’t be the sole owner of information, or at least not for that long.

To restore, or simulate, the feeling of scarcity of accessibility to information we resort to premium contents, reserved to members, be they simple subscribers or even paying members

All that is scarce is not gold…

We have said what scarcity is, perhaps we need to reiterate what it is not. It is certainly not hiding information from the user.

Sure, this is neither the place nor the time to open up the gigerenzian debates. Nor do we want to trigger a discussion about how ethical it is to leverage our cognitive biases, after all, persuasion has been around since the dawn of time (…and an impulse buy on Amazon has never killed anyone). But there’s certainly a big difference in presenting users with real data about the actual availability of a product or deliberately creating scenarios to increase the perception of scarcity. Unquestionably, in the immediate term, it might spur one, ten or a thousand users to conversion, but what happens to brand reputation and our ability to demonstrate empathy in the long run?

The appropriation by the disciplines of concepts that were so far of exclusive reserve of the world of psychology is undoubtedly an excellent means of contamination and has allowed UX design to create smooth, user-friendly, immersive and enjoyable browsing and buying experiences. But there’s one thing we mustn’t forget: every aspect of human behavior must be studied and tested by the appropriate means, what works for one environment might not be as successful in another context. As Teodorescu reminds us, we must never stop testing what is best for our users. And, we would add, we should be wary of those who present us with these heuristics as the absolute and final panacea for our e-commerce sites.

The products and services included in the article are purely for demonstration purposes, in no way does the author or the blog undertake commercial relationships with brands or marketplaces reported here as examples of the phenomena described. Thirsty for more? Take a look at the “UX Collective” thread on Medium.com. This article was inspired by UX designer David Teodorescu's work and was first published in the Italian Version of the BE-Blog. Still here? Ok. Here you go. Cialdini, R. B. (2001, February). The science of persuasion. Scientific American, 284, 76-81; Lynn, M. (1989). Scarcity effects on desirability: Mediated by assumed expensiveness?. Journal of Economic Psychology, 10(2), 257-274; Wu, W. Y., Lu, H. Y., Wu, Y. Y., & Fu, C. S. (2012). The effects of product scarcity and consumers’ need for uniqueness on purchase intention. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 36(3), 263-274; Gleick, J. (2012). The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood

About the author

Serena Iacobucci

Serena Iacobucci holds a PhD in Business & Behavioral Sciences from the Department of Neurosciences, Imaging and Clinical Sciences (University of Chieti, Italy) – where she is currently Post-Doc in Behavioral Economics and Member of the Behavioral Economics Lab and teaching assistant in Behavioral Economics and Finance. She is currently working on the individual factors involved in the perception and detection of fake content, with a specific focus on sensitivity to semantic nonsense, such as BS-receptivity.

She is editor and contributor of the BE-Blog and the Italian Behavioral Economics Blog, associate editor of the Italian version of the online quarterly magazine for psychology InMind.

She is content creator for Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram of the mentioned blogs and journals and she works and Social Media, Communication and Linguistics consultant for the Neuromarketing Agency Umana-Analytics.